Good morning from… Can you guess where in Africa this is? (Answer at the bottom!)

The Blue Train’s Window Into South Africa’s Fragmented World

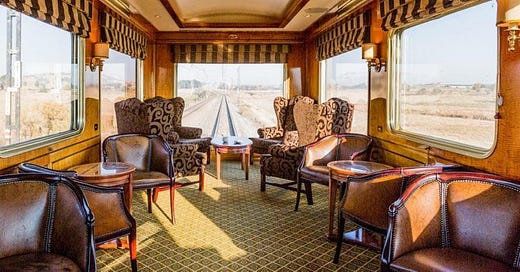

The Blue Train promises indulgence: crystal glasses, marble-tiled bathrooms, and panoramic views of South Africa’s jaw-dropping landscapes. But for one journalist riding the legendary rail from Cape Town to Pretoria and writing for The New York Times, the trip was also a rolling meditation on inequality, history, and what has—and hasn’t—changed since apartheid.

Past the chaos of Cape Town’s bus terminal, behind a security gate and a velvet rope, guests were greeted with sparkling wine and butler service. It was a scene of curated serenity: piano music, plush sofas, and a sharp line between the affluent few inside and the informal workers and commuters outside.

That contrast set the tone for the journey. Because while the Blue Train rolls through South Africa’s spectacular beauty, it also slices through some of its harshest realities.

Luxury, for Some: Prices start at $4,000 per couple and can climb past $6,000. With seven meals, free-flowing drinks, and bathtubs with golden showerheads, the Blue Train caters to a select crowd. On this trip, the author and his wife were two of only four Black passengers. Nearly every other traveler was white—mostly foreign. Nearly every staff member was Black or coloured.

Decades after apartheid’s formal end, the economic and racial disparities that defined it are still easy to spot—even on South Africa’s most glamorous train.

The train was delayed after being pelted with rocks near the station—possibly just mischief, but symbolically rich. It underscored a painful point: luxury in South Africa often exists in full view of poverty, and the gap between the two can provoke resentment, if not outright anger.

Eventually, the ride crossed verdant wine valleys, arid plains, and historic sites like Kimberley’s Big Hole—once the world’s richest diamond mine, now a crater of complicated memories. A plaque there acknowledged the laborers who died digging it out, offering a rare nod to the exploitative roots of South Africa’s wealth.

Ultimately, the Blue Train is a marvel. But it’s also a metaphor. It glides past tin-roofed shacks and derelict rail towns, wind farms and solar fields, each snapshot offering a glimpse into the country’s past and possible future. There’s no time to stop and unpack the complexity—you see what you see, and you keep going.

The journey makes for a fascinating read, and you can find the article right here.

Musk vs Malema: How a Struggle Song Became a MAGA Rallying Cry

When Elon Musk tweets, the internet listens—including when he's weighing in on South African politics from a few continents away. This week’s episode of “Billionaire Tweets Through It” featured Musk calling out “a major political party … actively promoting white genocide,” complete with a video of South Africa’s Julius Malema singing the controversial anti-apartheid song Dubul’ ibhunu—translated as “Kill the Boer.”

The usual suspects—Trump and Rubio—soon followed, with Rubio urging Afrikaners to flee South Africa and settle in the US, while Trump reposted the clip to his followers.

But what is this song, and is it actually calling for genocide, or just a politically inconvenient remix from the apartheid-era archives?

Dubul’ ibhunu emerged in the 1980s, when apartheid was still a fully operational nightmare. “Boer” literally means “farmer” in Afrikaans, but politically, it’s shorthand for “white oppressor” in the context of South Africa’s past. The lyrics? Not subtle. Lots of “shoot the Boer” repetitions, often accompanied by protest dancing and mimed gunfire.

But for many in South Africa, it’s less a threat and more a historical throwback—a way to assert political identity, however controversial.

Julius Malema’s no stranger to controversy: He first belted out Dubul’ ibhunu in 2010 while still with the ANC Youth League. Since then, he’s made it something of a signature EFF battle cry—an attempt to outflank the ruling ANC and brand himself as the raw, unfiltered voice of South Africa’s Black working class.

When Musk tweeted, Malema had just performed the song again at a rally commemorating the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre—a moment of brutal apartheid violence that’s now marked as Human Rights Day in South Africa.

So... Is This Hate Speech? Depends on who you ask—and which court you’re in. Malema’s been sued over the song multiple times. Earlier rulings called it hate speech. But in 2022 and again in 2024, South African courts ruled in his favor, saying a “reasonably well-informed person” would understand the song as historical performance, not a literal hit list.

Why Are Musk, Trump, and Rubio So Invested?

Short answer: optics.

Longer answer: South Africa has become a pawn in America’s domestic culture wars. The idea of a white genocide abroad plays nicely into the victimhood narrative that fuels the MAGA base. Never mind that South Africa sees 19,000 murders a year and only about 60 of them are farmers—of all races. Or that AfriForum, the white minority rights group, hasn’t gone as far as Musk or Trump in their genocide claims.

For Trump and Musk, it’s not about South Africa. It’s about South Africa as a metaphor for what happens when DEI goes “too far.”

Welcome to Ivory Coast 2.0, The African Country Doing Just Fine

When Bernard Ayitee’s parents moved to Ivory Coast in the 1980s, the place was riding so high it got an actual nickname: the “Ivorian Miracle.” Imagine an economy so hot that even French economists temporarily forgot to be cynical. Fast forward through two civil wars and a mass exodus, and Côte d’Ivoire is once again flashing that old miracle sparkle, if not the entire fireworks show.

Ayitee himself grew up among cocoa fields and cameos of Abidjan’s city lights, then trotted off to France for schooling. A decade ago, as if hearing a clarion call, he boomeranged back—alongside plenty of others who sensed a serious upswing. “This country is blessed,” the 38-year-old insists. “Anything you try can work.” Slightly hyperbolic? Maybe, but Ivory Coast’s stats do back him up.

Ivory Coast is the region’s improbably cheerful outlier. After near total collapse in two nasty wars (2002–07 and 2010–11), it somehow hopped straight back on the growth train at an impressive 7% annually for more than a decade. It breezed through COVID while the rest of us were quietly chewing anxiety pills. Meanwhile, inflation is under 4%, whereas West Africa’s is around 22%. For a country of 31 million? That’s magical.

Yes, Ivory Coast is the world’s cocoa king, but that’s old news: Services now make up over half the economy; manufacturing’s creeping up. So, even if the cocoa harvest crashes or global prices tank, Ivorians have other tricks.

And while some countries in the region struggle to coax in a single honest investor, Ivory Coast has bagged more private investment than any other Francophone West African state, with foreign firms sinking money into everything from fintech to packaging. You have to give the president some credit: Alassane Ouattara, has pitched Ivory Coast to foreign investors like he’s selling a timeshare, offering tax and customs sweeteners, and apparently the approach works. Airports, roads, and flashy new bridges are materializing like mushrooms after a monsoon. The 83-year-old boss also boosted the power grid: 34% had electricity in 2013, but now it’s close to 94%. That’s a monstrous leap forward in a decade.And although it might not thrill climate activists, Ivory Coast has found oil off its shores, and plans to produce up to 200,000 barrels a day in a few years.

All right, it’s not entirely a utopia. The younger generation’s skill set took a hit from the wars’ disruption of schools, so businesses fret about workforce quality. And the potential shift toward heavy oil exploration might come back to bite them if (or when) the world starts punishing big emitters.

And there’s the elephant in the room: Ouattara secured a third term in 2020 despite a constitution that kinda says two terms is the limit. This year’s election might see him try for a fourth. Meanwhile, ex-President Laurent Gbagbo—the man whose refusal to concede the 2010 vote launched the second civil war—also wants back in, presumably for “unfinished business.”

But if Côte d’Ivoire can handle that transition, it will continue to be the envied cousin at the African family gathering, sporting low unemployment and talk of soon reaching middle-income status.

Food for Thought

“To give is to save.”

— Namibia Proverb

And the Answer is…

The photo is taken in Nairobi, Kenya! You can also send in your own photos, alongside the location, and we’ll do our best to feature them.