🔅 South Africa’s “Unforgotten” Get Their Due

1,500-Year-Old Manuscripts on the Run & The London Naija: When Football Becomes Home

Good Morning from Zanzibar!

The 1,500-Year-Old Manuscripts on the Run: Tigray’s Hidden Treasures

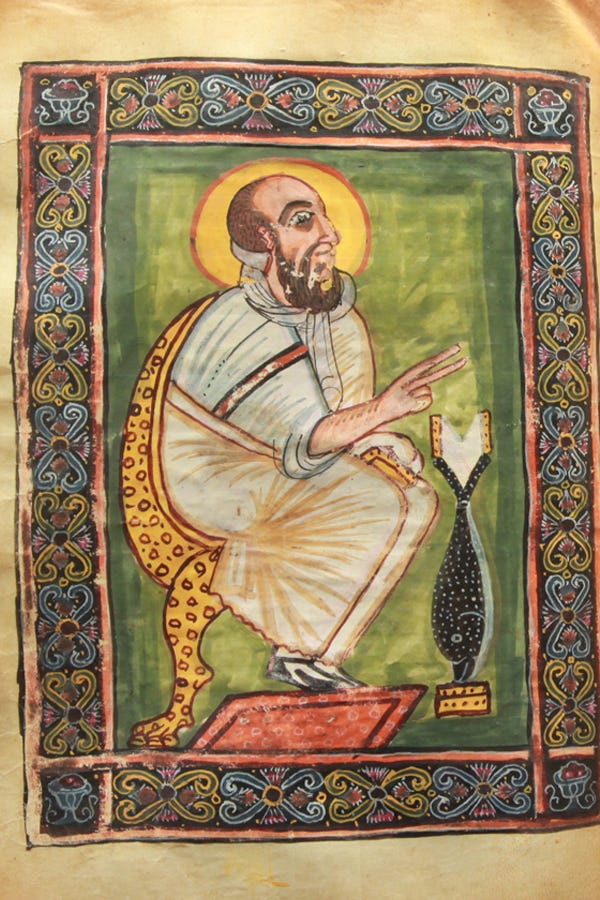

If you think your cherished family heirloom is precious, wait till you hear about the Garima Gospels—a set of beautifully illustrated Christian manuscripts believed to be the oldest complete of their kind on Earth. For centuries, they’ve been tucked away in the Garima Monastery atop a mountain in northern Ethiopia’s Tigray region. The Gospels were guarded like VIPs by Orthodox monks who’ve always sworn by their protective saint, Abune (Saint) Garima.

But in November 2020, war came knocking. Cue Father Gebretsadik, who realized these priceless manuscripts needed an immediate getaway plan. After all, if marauding soldiers have a weakness, it’s for stealing or destroying anything that looks remotely valuable—especially if it’s 1,500 years old and famously holy.

When Life Hands You War…

In late 2020, Tigray became embroiled in a brutal conflict that erupted between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. Throw in some Eritrean troops itching to settle old border scores, and you’ve got a recipe for chaos.

Historically, the monks had always kept the Garima Gospels securely inside the monastery, trusting the power of Saint Garima and the rugged mountain terrain to fend off any invaders. This time, though, Father Gebretsadik and friends decided they couldn’t chance it. Under cover of darkness, they smuggled the Gospels out—the first time ever in recorded history—and hid them so thoroughly that Indiana Jones would never be able to find them.

Why all this fuss? The Garima Gospels date back about 1,500 years, penned in the Geez language (basically the vintage version of Ethiopian liturgy). According to local lore, Saint Garima himself whipped up these manuscripts in a single day after praying the sun into a brief standstill.

In more peaceful times, visitors could view these manuscripts in a little museum at the foot of the monastery’s steep stone steps. But since the war, the museum’s been empty and dusty.

“Has Saint Garima Abandoned Us?”

This question weighs heavily on everyone who survived. The saint who was supposed to watch over them seemed MIA—right alongside the Gospels. Families who lost relatives wrestle with a sense of cosmic betrayal: “We prayed every day, so why didn’t he protect us?”

In Ethiopian Orthodoxy, saints are often go-betweens for humans and the divine. If the Garima Gospels are physically gone, it’s as if Saint Garima himself is on an indefinite vacation. Some locals see the absent relics as a sign that the saint’s blessing has paused.

So, where are these ancient texts now? Possibly sealed in mountain caves near Adwa, maybe buried underground, maybe tucked away in someone’s secret crawlspace. Only a handful of monks know, and they’re not about to give up the location to anyone, let alone prying journalists or foreigners who might have sticky fingers.

And you can read more on this fascinating episode here.

South Africa’s “Unforgotten” from WWI Finally Get Their Due

Just imagine you know your relative went off to fight in World War I, but there’s zero trace of them—not a headstone, not an official grave, not even a grainy black-and-white photo. All you’ve got is the family rumor that they “went to war and never came back.”

That was the heartbreaking reality for many Black and Asian families across Britain’s old empire—until now. More than a century after their ancestors’ wartime heroics, 1,700 mostly Black South African soldiers have finally been commemorated in a brand-new memorial in Cape Town.

When “Equal in Death” Didn’t Quite Happen

Way back in 1917, the (now) Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) was supposed to ensure everyone got the same honoring in death. But guess what: “pervasive racism” scuppered that plan. Some folks in charge at the time figured Africans were too “uncivilized” to appreciate gravestones.

The result? Up to 350,000 African and Asian casualties went uncommemorated or only got a half-hearted mention. Fast forward to a 2019 documentary that yanked this major oversight into the spotlight, followed by a 2021 investigation revealing just how widespread the problem was.

To right these wrongs, the CWGC has built a striking memorial in Cape Town’s Company’s Garden, complete with tall wooden posts engraved with names and dates.

Local historian Sonwabile Mfecane helped track down surviving descendants. Some assumed their ancestors had been lost in the high-profile SS Mendi disaster—a troopship collision off the English coast in 1917. Then they learned the real story, including some rather uncomfortable details about how their relatives died.

One of them said these revelations finally explained those recurring nightmares they’d had—like a spiritual puzzle piece falling into place. In many African cultures, not properly commemorating your dead can leave entire families (and generations) feeling…haunted.

Now, they say, the ghosts can rest.

The Bigger Plan: Sierra Leone and More

This is just the start. The CWGC is also working on a memorial in Freetown, Sierra Leone, for another 1,100 service members, and investigating up to 90,000 (!) uncommemorated folks from East Africa.

While no memorial can bring lost loved ones back, a proper commemoration can help families—and entire communities—close a century-long wound. As historian Sonwabile puts it: “We close the chapter and let the deceased proceed.”

The London Naija: When Football Becomes Home

They came from Nigeria in the 1980s with plans so modest you could tuck them into your back pocket: get a decent education, earn a bit of money, and maybe—just maybe—head back home. But London is a big city full of small surprises. Those short-term “just passing through” ambitions quickly turned into two jobs and part-time study, endless nights and early mornings, and eventually a permanent claim on this corner of the UK.

Over the decades, Nigerian families put down serious roots in London—raising kids, hosting parties, burying relatives, forging new traditions. Sometimes they left again, lured by “home” across the sea. Often, they stayed, grappling with a sense of in-betweenness: loyal to Nigeria yet comfortably at ease in Battersea or Brixton.

In a fantastic piece in The Guardian, this writer explains why football is the living, breathing stage where all these resulting identities overlap. And why it is, in itself, home.

Food for Thought

“Effort and capability are not the same.”

— Kenyan Proverb