Image of the Day

Spotlight Stories

The Mastermind Behind South Africa's "Great Bank Heist" Gets 15 Years in Prison

Tshifhiwa Matodzi, the former chairperson of VBS Mutual Bank, has been sentenced to 15 years in jail for his role in the $130m (£100m) banking scandal that rocked South Africa in 2018.

The scam, which stretched from impoverished rural villages to government circles, defrauded ordinary South Africans and caused national outrage.

Matodzi pleaded guilty to 33 counts, including corruption, theft, fraud, money laundering, and racketeering. While his combined sentence amounts to a staggering 495 years (15 years for each count), the court ordered that the sentences run concurrently, meaning he'll serve 15 years in total.

The "Great Bank Heist"

The 2018 report that investigated the scandal dubbed it the "great bank heist," and for good reason.

VBS, once a modest mutual bank that helped rural communities secure mortgages and save for funerals, was allegedly transformed into a slush fund for corrupt politicians, local government leaders, and their business cronies.

The bank's owners were accused of bribing local officials in some of South Africa's poorest and most dysfunctional municipalities, persuading them to divert (or pretend to divert) their budgets into VBS's coffers in return for cash and gifts.

It was only when the central bank took control of VBS that investigators discovered the full extent of the alleged looting and political intrigue.

Matodzi was accused of masterminding the looting, with the support of a team of highly qualified accountants and lawyers, and a dizzying network of apparently fraudulent shell companies and subcontractors.

While numerous people had been arrested in the VBS case over the years, only Matodzi and former VBS chief financial officer Phillip Truter have been found guilty and sentenced.

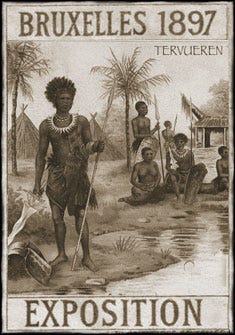

The AfricaMuseum's Reckoning: Grappling with a Violent Colonial Past

Ah, the AfricaMuseum in Brussels. Once a shining monument to Belgium's colonial exploits, now a museum wrestling with its dark history and the growing calls for restitution of its ill-gotten treasures.

Take, for example, the lustrous copper and glass necklace that graced the museum's displays for years. Its simple provenance story—acquired from a Greek resident of the Belgian Congo, who got it from a mechanic, who bought it from a Congolese chief—hides a much more sinister reality.

The necklace, it turns out, belonged to Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu, a Songye chief and proponent of Congolese independence who was hanged by the colonial administration in 1936. His family believes he would never have parted with the necklace voluntarily.

A Museum Founded on Violence

The AfricaMuseum, like many of its European counterparts, is grappling with the fact that a significant portion of its collection was acquired through violence and coercion during the brutal reign of King Léopold II in the Congo.

Recent research has revealed that more than 40,000 objects—about a third of the museum's entire collection—were collected during the most violent period of Belgium's colonial history. Thousands of artefacts were seized during punitive expeditions, and rubber traders like the notorious Compagnie du Kasaï made regular deliveries to the museum.

The museum's director, Bart Ouvry, acknowledges that restitution is inevitable, but he cautions that it will "take decades" to complete. Belgium has passed a law allowing for the return of objects acquired under duress or through violence, but the process is far from straightforward.

Curator Anne Wetsi Mpoma argues for a grassroots approach, with Belgian museums and the Congolese diaspora working directly with African museums and local communities to transfer works. She questions whether the Congolese government is equipped to handle the returned objects and ensure they reach the rightful communities.

Meanwhile, the AfricaMuseum is attempting to revise its own displays, moving controversial colonial-era sculptures and busts to a storeroom where they can only be seen as part of a guided tour. But as Ouvry admits, it's a process, and the museum cannot afford to remain in its ivory tower.

The AfricaMuseum's reckoning with its past is a microcosm of the larger debate around the restitution of colonial-era artefacts. It's a messy, complicated process that requires confronting uncomfortable truths and working towards a more equitable future. But as the saying goes, the first step is admitting you have a problem.

Food for Thought

“Even the lion, the king of the forest, protects himself against flies."

— Ghanaian Proverb

Hi