Good morning from… can you guess where? (Answer at the bottom!)

Marlene Dumas Just Shattered a Glass Ceiling… With a $13.6 Million Paintbrush

If you're keeping score in the world of art auctions (or feminism, or South African excellence), make sure to write this one in bold: Marlene Dumas has officially become the highest-selling living female artist after her painting “Miss January” sold for $13.6 million at Christie’s.

That’s right. While most of us are still trying to frame our posters straight, Dumas’ emotionally complex, nine-foot-tall ode to womanhood just made history.

Painted in 1997, “Miss January” is considered Dumas’ magnum opus, a kind of feminist mic drop that reclaims the female nude from its long-standing status as ‘something to be stared at by old men in museums.’ Christie’s described it as a work that masterfully portrays the female body while giving it the narrative power it has long been denied in art history: less objectification, more confrontation.

However, while $13.6 million is a lot of money, at the same auction, a Jean-Michel Basquiat piece went for $23.4 million, and Jeff Koons still holds the “living artist” world record at $90.3 million for his shiny silver bunny. (A bunny!)

The auction thus reopens the age-old question: why do artworks by women still sell for about 10% of what male artists fetch? That gender gap, as a 2022 BBC documentary pointed out (Recalculating Art), isn’t just about who paints better. It’s about who the art world decides to value.

For now, though, let’s celebrate a well-earned win. One powerful portrait, one powerful price tag, and one very proud continent.

Nigeria’s Cannes Breakthrough: “My Father’s Shadow” Puts Nollywood on the Croisette Map

Looks like Nigeria just crashed the Cannes party in style. “My Father’s Shadow,” the feature debut of director Akinola Davies Jr., is officially the first Nigerian film ever to land in Cannes’ prestigious Official Selection (Un Certain Regard, no less).

One day, one city, one giant “what-if”:

Set on 12 June 1993 (Nigeria’s most infamous election-that-never-was) the film imagines two young brothers spending a single, life-changing day with the father they barely knew. Thing is, the film is semi-autobiographical, with real-life siblings Akinola and Wale Davies mining half-remembered stories, half-invented dreams, and a stash of family lore to craft the script.

The result is a history-maker, this being the first Nigerian film ever invited to Cannes’ Official Selection. (We’re still awaiting to see the volley of “Nollywood’s gone global” headlines.) Moreover, every key crew member hails from Nollywood, silencing anyone eager to label the project “too international.” Already, streamer-cinephile darling Mubi has snapped up North American rights before the premiere, proof the buzz isn’t just local chest-thumping.

Nigeria’s film sector already pumps out more titles per year than Hollywood. Cannes visibility means bigger budgets, bolder stories, and maybe – just maybe – a future where “Nollywood” isn’t prefaced with “Africa’s answer to.” It simply is cinema.

Can’t wait to see it!

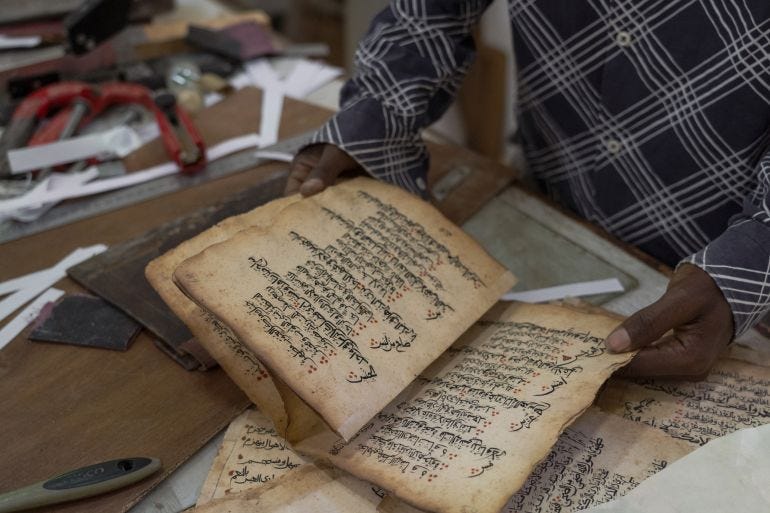

The Bookbinder of Harar: How Abdallah Ali Sherif Rescued a Vanishing Library

For most of his childhood, Abdallah Ali Sherif was told Harar had no past worth mentioning. Islamic schools were closed, mosques repurposed as churches, and anyone who asked too many questions risked prison. But once Ethiopia’s post‑1991 reforms loosened the gag, Sherif, then in his 40s, went on a one‑man quest to prove his parents wrong.

Rebuilding a Lost Archive

The hunt: Sherif roamed Harar’s ochre alleys buying (and later receiving) heirloom Qurans and legal texts that families had hidden for generations.

The haul: He has amassed about 1,400 manuscripts, the largest single trove of Harari Islamic texts on Earth, including a Quran more than a millennium old.

The craft: Noticing most volumes were falling apart, Sherif revived the extinct local art of bookbinding. He tracked down the last pupils of a long‑dead master binder, trained in Addis Ababa and Morocco, then perfected the tradition himself.

In 1998 he opened a tiny private museum in his house; by 2011 the regional government handed him Haile Selassie’s father’s former mansion. The Abdallah Sherif Museum now doubles as a conservation lab where Sherif and his protégé Elias Bule restore decaying tomes, imprinting fresh leather covers with century‑old Harari stamps.

Here’s Why It Matters

Once a center of Red Sea–to–Indian‑Ocean scholarship, Harar’s manuscript culture all but died after the city fell to Emperor Menelik II in 1887 and later under Haile Selassie and the Derg. Sherif’s collection reconnects Hararis to their intellectual heritage and offers scholars a rare window on Indo‑African calligraphy, Ajami texts, and local Islamic jurisprudence.

At 75, Sherif has trained dozens of youths in the ancient craft, digitized nearly every manuscript, and turned his museum into a hub of heritage pride. Every book he rescues, he says, “adds a missing piece to a puzzle,” and you can read more about this amazing man on Al Jazeera’s website.

Food for Thought

“If you sleep, your business sleeps too.”

— Zambia Proverb

And the Answer is…

The photo is taken from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania! You can also send in your own photos, alongside the location, and we’ll do our best to feature them.