🔅 From Poetic Patrimony to Gulf States' Influence

Senegal's Senghor Library, Farmers' Climate Adaptation, and the US Dilemma in Gulf-Africa Ties

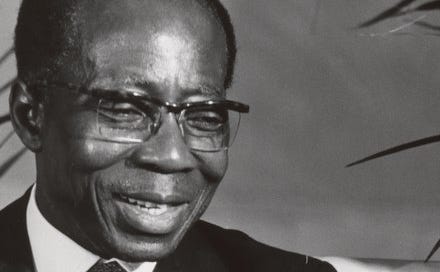

Photo of the Day

Spotlight Stories

Senegal's Poetic Patrimony: Bringing Senghor's Library Home

Imagine you're a newly elected president, and you find out that a piece of your country's literary heritage is about to be auctioned off in a foreign land. What do you do? If you're Senegal's Bassirou Diomaye Faye, you step in and negotiate a deal to bring the collection home.

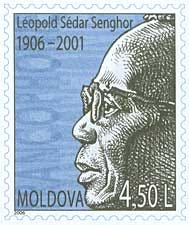

The library in question belonged to none other than Léopold Sédar Senghor, the first president of independent Senegal and a founding father of the Négritude black consciousness movement. Senghor spent the last 20 years of his life in Normandy, France, and his library of 344 volumes was set to go under the hammer in mid-April.

This wasn't just any old collection of books. Among the volumes were works personally inscribed by authors like Martinican poet Aimé Césaire, Senghor's fellow Négritude pioneer. These books chronicle the emergence of a movement that celebrated black identity and culture in the face of colonial oppression.

Senghor's Scattered Legacy:

Senghor's heritage is spread across two continents, with artifacts and archives divided between France and Senegal. While his former home in Dakar has been open to the public since 2014, the house in Verson, where he spent his final years with his French-born wife, remains mostly closed.

Last year, Senegal's government had to intervene to stop another auction of Senghor's personal effects, shelling out €240,000 to bring home 41 objects, including medals, pens, and jewellery. It's a bittersweet situation, as Labrune-Badiane notes: "From Senegal's perspective, it's tough to understand why Senghor left the entirety of his estate in France. The fact that the Senegalese state has had to buy it back rankles a bit."

But Senegal is determined to honour Senghor's legacy, with plans to incorporate his library into a museum dedicated to his life. As Senegalese ambassador to France El Hadji Magatte Seye put it, "Even beyond these particular assets, we believe that Senghor himself constitutes an inheritance: Senegal's heritage, Africa's heritage, the world's heritage. Saving it from being broken up was essential."

And what a heritage it is. Senghor was not only a statesman but also a poet, cultural theorist, and intellectual giant. His archives, including early drafts of his work written from the late 1950s onwards, offer a window into Senegal's history from the '60s to the '80s.

From Fertilizer to Forgotten Crops: How African Farmers are Adapting to Climate Change

As climate change wreaks havoc on the heavily agriculture-reliant African continent, farmers are turning to both ancient practices and modern technology to ensure food security for the booming population.

In drought-stricken Zimbabwe, where millions face hunger, small-scale farmer James Tshuma has found success in his small garden, despite losing hope for his fields. The secret? Homemade organic manure and fertilizer made from previously discarded items like livestock droppings, grass, plant residue, and even animal bones. "This is how our fathers and forefathers used to feed the earth and themselves before the introduction of chemicals and inorganic fertilizers," Tshuma explains.

Climate change is compounding sub-Saharan Africa's longstanding problem of poor soil fertility, forcing farmers to re-examine traditional practices and blend them with modern methods.

In addition to fertilizer techniques, farmers are also turning to drought-resistant crops like millets, sorghum, and legumes, which were once staples before being overtaken by exotic white corn in the early 20th century. Even the leaves of drought-resistant plants, once considered weeds, are making a comeback on dinner tables and in elite supermarkets and restaurants.

If you want to find out how other parts of Africa, like Somalia and Kenya, are adapting agriculturally to climate change, click this link.

Gulf States' Burgeoning African Relationship: A Boon or a Bane?

Last year, over 50 African leaders, a motley crew of democrats, dictators, reformers, and kleptocrats, all gathered in Riyadh for the first-ever Saudi-Africa summit. Their aim was to get their hands on a slice of the $40 billion pie that Saudi Arabia is offering them.

But there's more to this gathering than meets the eye.

The summit is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the growing economic and political ties between the Gulf petro-states and their African counterparts. The U.S., worried about China and Russia's growing influence in Africa, has actually been playing matchmaker, encouraging the likes of the UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia to step up their game on the continent.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

On the surface, this newfound love affair between Africa and the Gulf states seems like a win-win situation. Gulf countries bring their petro-dollars to the table, investing in everything from mining and agriculture to infrastructure. They've even managed to keep their airlines flying to all corners of the continent, even as COVID-19 grounded most other international flights.

But scratch beneath the surface, and you'll also find a darker side to this relationship. Gulf states may not be interested in meddling in African countries' internal politics, but they're not exactly champions of democracy and good governance either. In fact, some of them have been accused of fueling instability and humanitarian crises by backing armed groups in places like Sudan.

And then there's the issue of illicit financial flows. Dubai, the glittering city of gold, has become a major hub for smuggling networks that are siphoning off Africa's wealth. It's also a safe haven for corrupt African politicians and oligarchs looking to stash their ill-gotten gains.

The U.S. Dilemma: Counterweight or Millstone?

Washington finds itself in a bit of a bind when it comes to the Gulf-Africa relationship. On the one hand, it wants to use Gulf states as a counterweight to China and Russia's growing influence on the continent. On the other hand, it risks undermining its own stated commitment to promoting democracy and good governance in Africa by turning a blind eye to the less savory aspects of Gulf states' involvement.

And so, the U.S. seems to have chosen the path of prioritizing great power competition above all else. But this short-sighted approach could end up being a millstone around its neck in the long run. Instead of giving Gulf states a free pass to do as they please in Africa, Washington could instead be using its influence to ensure that their activities bring sustainable growth and development.

Food for Thought

“When the shepherd comes home in peace, the milk is sweet."

— Ethiopian Proverb