🔅 Reimagining Architecture at the Venice Biennale

King Leopold’s Playbook to Mentally Enslave Africa

Good morning from… can you guess where? (Answer at the bottom!)

Kenya and Britain Reimagine Architecture at the Venice Biennale

At this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, the stately British Pavilion (usually a platform for showcasing the UK’s most polished architectural exports) has been disrupted, cracked open by a conceptual fault line running from Nairobi straight through empire, extractivism, and climate collapse.

For the first time ever, the British Council has handed the curatorial reins to a team split between Kenya and the UK. Leading the charge: Stella Mutegi and Kabage Karanja of Cave Bureau, a radical Nairobi-based architecture practice, joined by UK-based geographer Kathryn Yusoff and architecture scholar Owen Hopkins. Their exhibition, titled Geology of Britannic Repair (GBR) is a reckoning.

Their premise is that colonialism isn’t just a moral and political problem. It’s a geological one too. Cities, mines, railroads, carbon emissions, labor systems – all of them moved earth, tore open landscapes, laid concrete over culture, and restructured ecosystems. For centuries, Britain led that charge.

The Rift

The exhibition’s conceptual launch point is the Great Rift Valley that runs through East Africa. And Cave Bureau and their collaborators are taking cues from location-specific (often overlooked) traditions, and elevates them as intellectual, architectural powerhouses. Their approach asks what futures might emerge by looking back – to before colonial borders, before concrete, before the commodification of land.

🤯

The fact that this work is being staged in the British Pavilion isn’t lost on the curators. The dialogue, it seems, will be: geopolitics meets geology, and empire meets accountability.

Mutegi is clear: “Kenya can’t do it alone. The UK can’t do it alone. Everyone has to be at the table.”

The exhibition also questions the rules of the Biennale itself. Why do only 29 countries get permanent pavilions in the Giardini? Why are Africa’s contributions so scarce? Who decided what counts as architecture?

Seems to us like this is a blueprint for repair. And it starts with a crack.

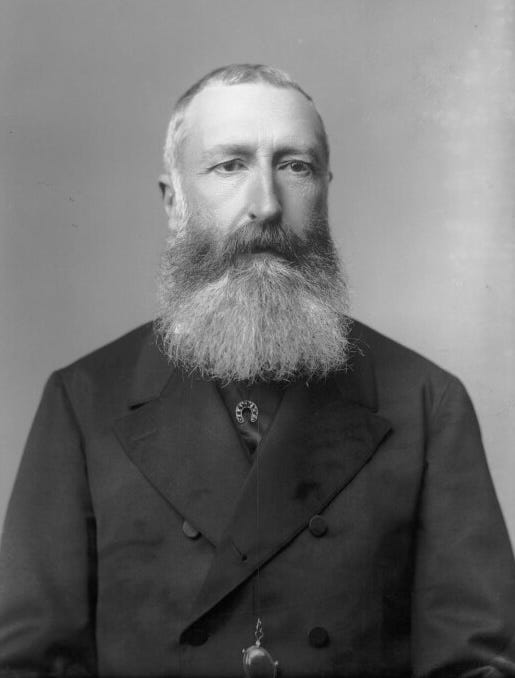

King Leopold’s Playbook: How Religion Was Weaponized to Mentally Enslave Africa

In 1883, while European empires were scrambling for African land like kids at a birthday party, King Leopold II of Belgium had a different kind of scheme: colonize not just the land, but the mind.

A letter allegedly written by Leopold to colonial missionaries, discovered decades later in a secondhand Bible in the Congo, reveals a blueprint for psychological warfare dressed up as religious salvation. (Historians still debate its authorship, but the vibe checks out.)

Leopold’s message to the missionaries was crystal clear: don’t bother teaching Africans about God. Instead, use Christianity as a tool to make them docile, poor, and dependent. Preach poverty. Preach submission. And make sure nobody gets any ideas about the wealth buried under their own feet.

His foremost objective: Targeting kids. Get them young. Train them to obey the missionary first, forget their ancestors, and swap their heroes for colonial ones. And under no circumstances, he warned, should Africans be allowed to think critically, only to read and recite without questioning.

Fast-forward to today and you can still see the echoes: African traditions sidelined as "pagan," foreign churches towering over local customs, and a version of religion that sometimes preaches patience over protest.

To read the letter, follow this link.

Mini-Grids, Mega Impact: How Tiny Solar Systems Are Powering Up Africa

Take one remote Zambian village called Chitandika. Add a few strips of solar panels. Stir in an entrepreneurial store owner – and voilà, you’ve got a microcosm of Africa’s latest push to electrify the continent. Gone are the days of darkness, studying by candle, and hauling a gas-guzzling generator in the trunk. In places like Chitandika, mini-grids have turned the lights on.

Meet Damaseke Mwale, who seized the moment when a solar mini-grid rolled into town. He not only built a new home and a grocery store but now charges an admission fee to watch televised soccer matches in his micro “cinema.” His kids’ school grades soared (unlike the local soccer team) because – guess what? – they can actually study after sundown. Think of the mini-grid as a literal bright idea fueling local nightlife, mini-market expansions, and improved test scores.

If Mwale’s story sounds like a blueprint for the rest of Africa, that’s because the World Bank sure hopes so. They’re championing “Mission 300,” an ambitious plan to help connect 300 million Africans to electricity by 2030. And they’re dangling the promise of up to $85 billion in potential funding to back it. The catch? Countries need to play nice with the private sector, set competitive tariffs, and (you guessed it) actually welcome solar.

Across rural African outposts from Zambia to Malawi, solar panels are turning once-silent villages into bright mini-hubs. Think barbershops open after dusk, kids learning computers without a roaring diesel generator in the background, and local teachers ditching flashlights for LED bulbs. As a result, more teachers want to live there, local businesses can crank out more services, and the economy gets a sweet jolt.

Some industry veterans say Africa may need upward of 200,000 mini-grids to reach that widely revered utopia of “energy for all.” Whether or not “Mission 300” hits the target by 2030 is up for debate, but the direction is clear: no matter if you’re sitting in a West African fishing village or an East African farmland, the future is bright – literally – if these solar startups keep hooking up the power.

Food for Thought

“One hundred aunts are not equal to one mother.”

— Sierra Leone Proverb

And the Answer is…

The photo is taken from Nigeria! You can also send in your own photos, alongside the location, and we’ll do our best to feature them.

Lots of interesting stuff in this newsletter. Good curation.