🔅 Africa’s ‘Unnavigable’ Rivers and Lakes: All Myth

And The Mystery of Sierra Leone’s First Family Fortune

Good morning from… can you guess where? (Answer at the bottom!)

🎬 Black Debuts, Big Gaps

Curator Rógan Graham’s new BFI season, Black Debutantes: Early Works by Black Women Directors, shines a light on a maddening mystery: Why do so many dazzling first features by Black women never get a follow‑up?

From Cauleen Smith’s coming‑of‑age jewel Drylongso to Bridgett M. Davis’s body‑positive Naked Acts, these movies crackle with wit, warmth and formal daring… then the directors largely vanish from the feature‑film landscape. The stats are brutal, and the careers are often one and done.

Still, these debut films pack a punch: They’re politically astute, emotionally layered, and formally inventive, whether it’s Ngozi Onwurah’s Afrofuturist Welcome II the Terrordome, or Jessie Maple’s quietly groundbreaking Will. And often, they circle recurring motifs: matrilineal tension, the gaze of the camera, and self-definition in the face of inherited trauma.

But curating the season wasn’t easy. Accessing these films required pirate Google‑Drive links, out‑of‑print VHS rips and sweet‑talking estates. Now, thanks to restorations and careful negotiations with families and estates, these films are back on the big screen.

Second‑feature syndrome still haunts the industry, and Graham notes that we’ve had a crop of beautiful debuts in recent years, but when checking IMDb, she wonders when the second film is coming…

If you can make it, Black Debutantes runs at London’s BFI Southbank from 1-31 May.

Africa’s ‘Unnavigable’ Rivers and Lakes: A Myth Debunked

Contrary to long-held assumptions, Africa has never lacked navigable waterways. From the Red Sea to the Niger River, and from Lake Victoria to the Atlantic coast, precolonial African societies built sophisticated systems of waterborne travel and trade, often eclipsing overland routes in scale and efficiency.

Along the eastern seaboard, Swahili coast mariners in places like Kilwa Kisiwani and Zanzibar crafted dhows that connected East Africa with Arabia, India, and Southeast Asia. Earlier still, Aksumite sailors moved goods from Sri Lanka and India to Roman ports in Egypt.

But while this coastal history is relatively well known, Africa’s internal river systems remain underappreciated. The Niger, Senegal, and Gambia Rivers formed a vast hydrological web that united regions as far-flung as Benin and the Hausalands. Sixteenth-century geographers even mistook them for one grand waterway: the mythical “Nile of the Blacks.”

In truth, they were navigated with purpose: Massive barges, recorded in Songhai chronicles and French travel accounts, moved 30 to 80 tons of cargo and people between cities like Djenné, Gao, and Timbuktu. One 19th-century traveler compared the bustle of the lower Niger to the upper Rhine. Boats measuring 100 feet long carried up to 80 passengers and their livestock.

Farther south, West-Central Africa’s Kwanza and Congo Rivers served as commercial lifelines for inland kingdoms like Ndongo and Kongo. Canoes and coastal sailboats formed a fluid trade network between Gabon, Cameroon, and Senegal. The Mpongwe of Gabon even built vessels so seaworthy, European visitors believed they could reach South America.

Similar waterborne traditions thrived around the African Great Lakes. Victoria, Tanganyika, and Malawi hosted a constant flow of traders, travelers, and navies. Lakeports flourished, and large dugout canoes and dhows carried goods and people across vast freshwater expanses.

breaks down how Africa’s rivers and lakes shaped kingdoms, connected regions, and it defies the myth of a continent sealed off from itself. You can read more on this here.From Council Flat to Coastal Mansions: The Mystery of Sierra Leone’s First Family Fortune

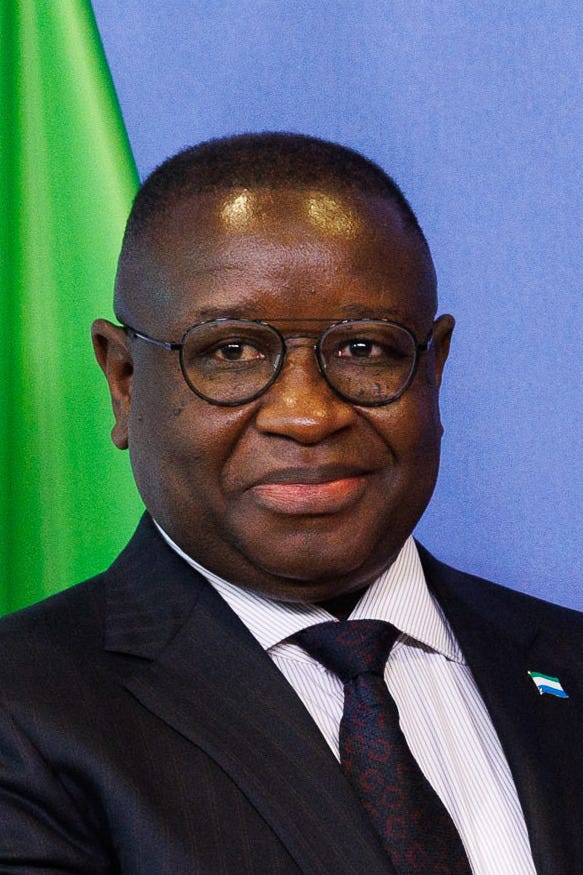

When Julius Maada Bio won Sierra Leone’s presidency in 2018, he and his wife, Fatima Bio, moved from a two-bed subsidised flat in south London to Freetown’s presidential lodge. Six years later, Fatima, her mother and half-brothers have quietly spent more than $2 million on at least 10 luxury properties along Gambia’s Atlantic coast.

The spending spree sits awkwardly with President Bio’s anti-corruption mantra. Officially, he draws only a state salary; Fatima receives no public wage. Their disclosed income, and that of her relatives, gives no hint of the cash needed for seaside mansions and hotel construction.

Questions multiply:

Fatima’s mother, Tidankay Darboe, listed as owner of a $500,000 villa, shows no taxable income in Gambia.

Half-brother Yusupha, once a Maryland hotel worker, paid $230,000 for the villa next door and registered a real-estate firm that reports almost no profit.

Half-brother Abdoul Mois Darboe revived a stalled hotel project and bought two high-end beach condos worth $650,000, yet his tax file logs only minor payments. He says the projects are “self-funded” from construction contracts, though no supporting records appear.

Meanwhile, Dutch authorities want Sierra Leone to extradite cocaine kingpin Jos Leijdekkers, photographed socialising with the Bios. The government says it is “reviewing” the request.

Sierra Leone’s anti-graft agency insists it has no active investigation; Gambian registrars rarely probe cash buyers. For now, the First Family’s property portfolio grows unchecked, and voters back home are left to wonder how a couple who once hosted birthday parties outside a London council flat can now bankroll a real-estate empire on West Africa’s most exclusive shoreline.

You can read the in-depth investigation right here.

Food for Thought

“You are bad if you are good only to yourself.”

— Zimbabwe Proverb

And the Answer is…

The photo is taken from Khartoum, Sudan! You can also send in your own photos, alongside the location, and we’ll do our best to feature them.