Good Morning from Zimbabwe!

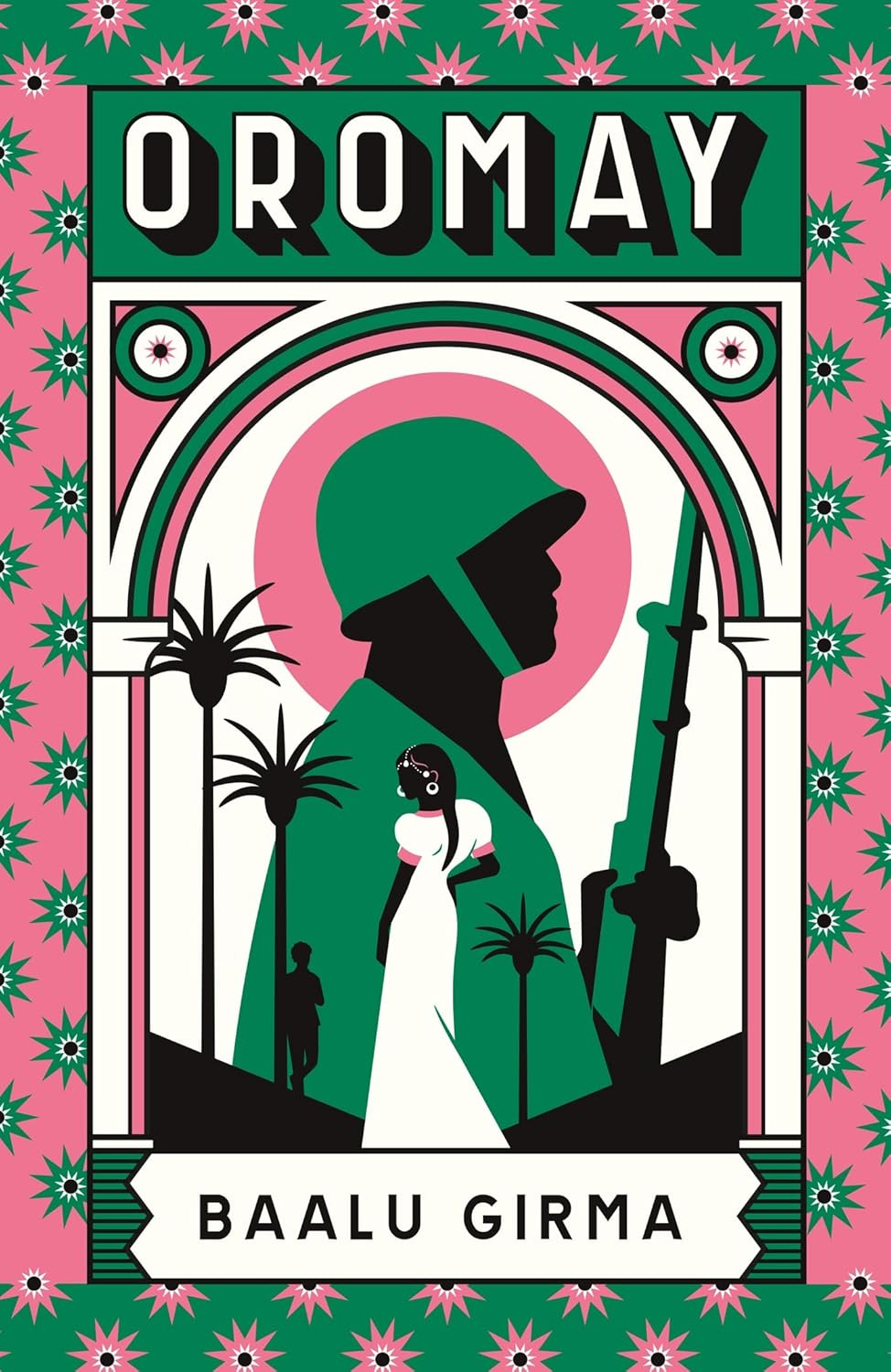

Oromay by Baalu Girma: A Brilliant and Tragic Satire

Baalu Girma's Oromay lands in English at last, delivering a gripping, satirical, and tragic exploration of propaganda during Ethiopia's civil war—an audacious work that likely cost the author his life. Part political commentary, part espionage thriller, the novel blends razor-sharp critique with the propulsive energy of a high-stakes drama.

The Plot: Set in 1982, Oromay follows Tsegaye, a television journalist thrust into a mission to win "hearts and minds" in Eritrea as part of the Red Star Campaign—a military propaganda initiative under Mengistu Haile Mariam's regime. The stakes are immediate and brutal: failure means not just the loss of a narrative war but the continuation of unimaginable violence. Through Tsegaye's eyes, the reader navigates the grim realities of Ethiopia’s civil conflict, where language and ideology are wielded as weapons.

The Language of Power

Baalu Girma, a journalist turned government insider, was uniquely equipped to dissect the propaganda machine he once helped operate. The novel’s prose reflects the perilous nature of words in this context—every phrase could save or end a life. As such, Tsegaye's deadpan delivery and moments of ironic self-awareness serve as both a critique of and a complicity in the machinery of state violence. This duality is a hallmark of the novel’s brilliance: it operates as propaganda for propaganda, yet its incisiveness peels away the facade of revolutionary ideals to expose the underlying horrors.

The strength of Oromay lies in its blending of fiction with the immediacy of journalism. The characters, though fictionalized, mirror real-life figures with unnerving accuracy. This authenticity, combined with the novel's relentless pacing, transforms it into a historical document disguised as an adventure story.

The novel’s unflinching portrayal of Ethiopia's Red Terror and the Eritrean resistance captures the trauma of a nation torn apart. Tsegaye’s gradual disillusionment reflects the betrayal felt by many young Ethiopians promised a better future through revolution. His final reflections—watching young men march to certain death—are haunting, a reminder of the devastating human toll of political ambition.

Suppression and Legacy

Upon its publication in 1983, Oromay became an instant sensation and an instant threat. Recognizing themselves in its pages, the regime suppressed the novel, arresting readers and confiscating copies. Baalu Girma himself disappeared six months later, his fate shrouded in the same darkness that enveloped the Red Star Campaign.

Forty years later, Oromay remains both a masterpiece and a tragedy, and The Guardian is re-releasing it here.

Soda: How One Festive Treat Became a Global Health Storm

Remember when sodas were break-out-the-confetti rare, like at Grandma’s big holiday bash? Now, in many places—think sub-Saharan Africa—kids can barely get through a school day without guzzling a fizzy sugar bomb. Billboards, TV ads, and even videogame pop-ups push the sugary stuff like it’s the next big celebrity fragrance.

Just How Bad Is It?

New research out of Tufts University dug deep into the Global Dietary Database, which covers 2.9 million people in 118 countries. The findings? Sugary drinks (we’re talking soda, energy drinks, juice cocktails that are mostly sugar-water) are tied to:

330,000+ deaths in 2020, and

3 million new cases of diabetes and heart disease that very same year.

Why the “Perfect Storm?”

Easy to Sip, Hard to Track: Liquid sugar hits fast, and it’s shockingly easy to ignore.

Mass Marketing Overload: Everywhere you look, there’s a shimmering can of sugar calling your name.

Outpacing Past Numbers: In 2015, sugary drinks were tied to 184,000 deaths—now it’s nearly double.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s Type 2 diabetes rates soared by nearly 9% since 1990, and heart disease edged up over 4%.

Study authors suggest policy measures like taxes on sugary beverages—similar to what we’ve seen in places like Mexico and some U.S. cities—could curb the onslaught. After all, these 3 million new disease cases “could have potentially been avoided” worldwide.

The Bottom Line

That everyday soda habit? It’s morphing from a fun fizz to a global health fiasco, especially in regions without the safety nets (or nutrition education) to handle the fallout, such as in Africa. The data’s in, and the next step may be pumping the brakes on that daily sugar fix—before we all end up paying a pretty hefty tab.

One African Expat’s Gaze at the Continent He Left Behind

Ever find yourself staring at a giant map of Africa pinned to your wall, squinting at all 54 countries and wondering how on earth you got here—far across the Atlantic with a plane ticket you may never cash in for a return trip? Welcome to the club.

Our author grew up in Lagos, Nigeria, where soda and Western music were once shiny novelties. Fast-forward to today, and he’s in the quiet suburb of Oxford, Mississippi, pursuing a PhD. That map on his office wall? It’s a daily reminder of where he came from—and how he’s part of Africa’s “newest lost generation,” people who left “home” for education and opportunity but remain haunted by everything they’ve left behind.

Conditioned for Exile?

Language Lessons

As a child, he was told to “speak only English” or face penalties—vernacular was seen as lesser. By 12, he was a grammar whiz, ironically knowing more about pop stars like Michael Jackson and Chris Brown than about indigenous heroes like Fela Kuti.Western Aspirations

Everyone told him that “in saner climes” (translation: places that actually work) he could thrive. Movies, radio shows, and that sweet “generator-powered TV” life all reinforced the message that real success = heading to the West.Rootlessness

Now, after crossing the Atlantic, he recognizes he’s disconnected from local cultures—both his own and those of other African nationalities. Meeting fellow African expats in Mississippi, he finds they share the same predicament: more knowledge of Western culture than their own.

The “Lost Generation” Vibe

He’s not alone. Many Africans his age are scattering worldwide, chasing degrees and stable jobs. Some folks call Nigerians “everywhere,” but the author clarifies: it’s not just hustle—it’s that many of them are “lost,” shaped to leave a land that failed them.

Sure, they might show up to an “Africa Night” in Western universities, but it’s mostly foreign outfits, foreign tunes, or a standoffish MC. They can’t read or write in their mother tongues with confidence. They avoid showcasing authentic traditions, having grown up worshipping the West.

Bottom Line?

For many young Africans, “home” is complicated. They were groomed to leave, clinging to global success but losing pieces of their heritage in the process. Now, from Mississippi or London or anywhere else, they look back at Africa on a map and wonder what might have been had they stayed—and what might still be if they ever go back.

It makes for a fascinating read.

Food for Thought

“If you do not gather fi rewood, you cannot keep warm.”

— Angolan Proverb